- Dec 21, 2025

Rummaging through a graveyard of ideas

- Clive Forrester

- Life

- 0 comments

Over the last ten years, I have dedicated three hours every week to the drums. I began as a complete novice, struggling to decipher the notation, but slowly taught myself the craft over the course of a decade. I am no virtuoso, certainly, but I can manage the occasional solo and hold a groove with a band at a moment's notice. I have developed a particular fondness for jazz and reggae, and I like to think I have a decent sense of rhythm.

The only problem with this story is that none of it is true.

At least, not in this universe. I did briefly own an electronic drum set in 2015, but I sold it when I had to move apartments. My expertise in percussion exists entirely in my head. It is a pity, really, because I suspect I could have been a decent drummer had I not abandoned the idea, leaving it to gather dust alongside so many others.

The Shadow CV

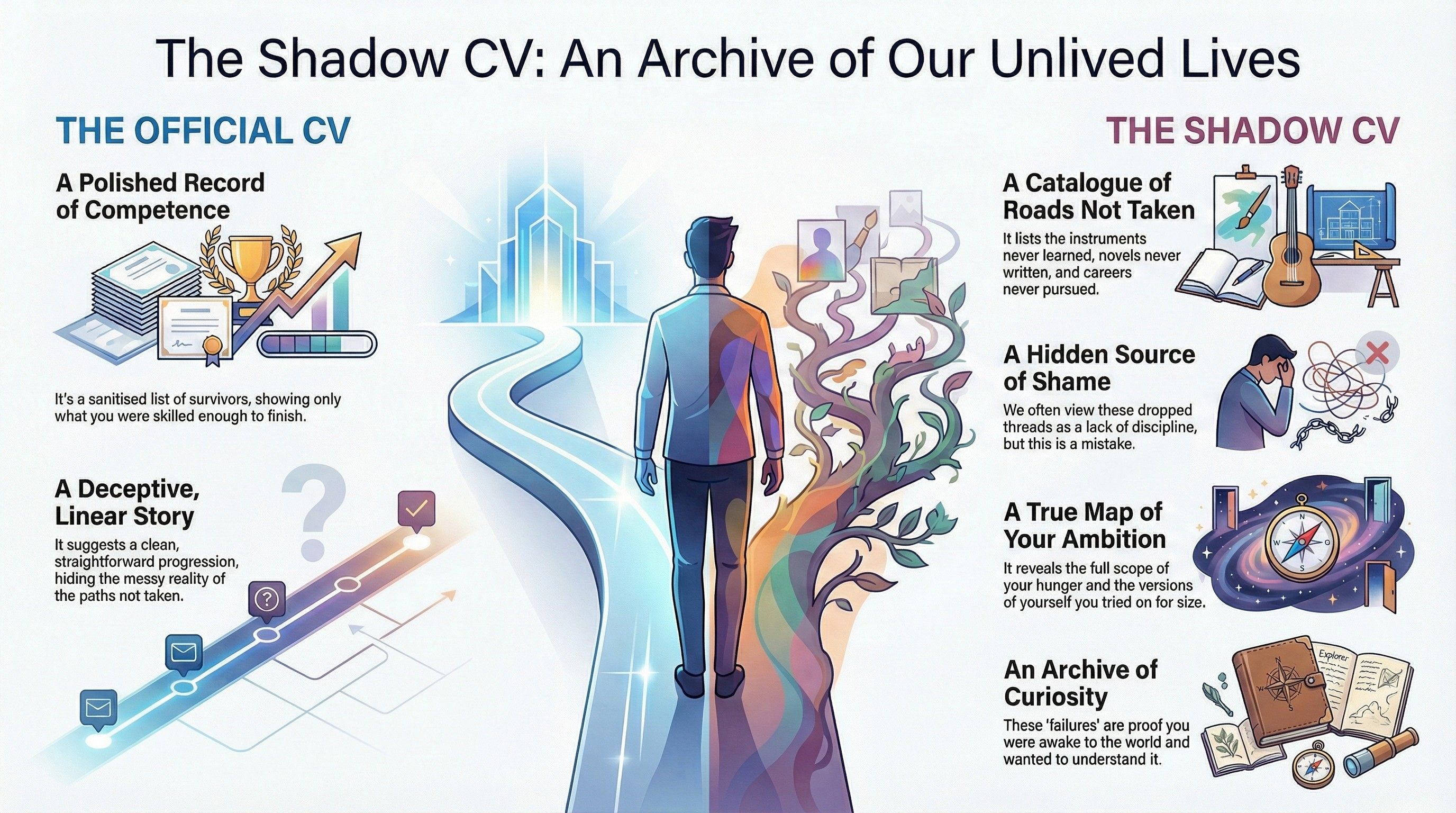

If you were to look up my professional history, you would find a tidy list of papers published and courses taught. It is a document that suggests a life of linear progression, a clean arrow pointing from graduate school to tenure. But this official record is, in a way, a deception. It is a list of survivors. It tells you absolutely nothing about the casualties.

I suspect we all carry around a second, invisible résumé—a Shadow CV. This document is invariably longer, messier, and much more honest than the sanitized version we post on LinkedIn. It is a catalogue of the roads not taken. It lists the novels we outlined but never wrote, the instruments we bought but never learned to play, the coding languages we studied for a month before getting bored, and the charitable foundations we planned to start but forgot about after a particularly busy week.

In my own Shadow CV, right next to that phantom drum career, you will find a brief but intense determination to become a corporate lawyer (abandoned 1998). You will find a screenplay about a time-traveling linguist that never made it past page ten (abandoned 2004). You will even find a passionate vow to learn tap dancing after watching the Gregory Hines film Tap—I even owned a pair of tap shoes (abandoned 2004).

We tend to view this Shadow CV with a deep sense of shame. We look at the debris of our past pursuits and see only a lack of discipline. We worry that these dropped threads make us look flighty or inconsistent. We hide them away, embarrassed that we couldn't stick it out. But I think this is a mistake.

The official CV is dull because it is merely a record of competence. It shows what we were good enough to finish. The Shadow CV is far more compelling. It reveals the full scope of our hunger. It shows the lives we considered living and the versions of ourselves we tried on for size. It is a map of our ambition, unconstrained by the petty realities of talent or time. We shouldn't view these abandoned projects as failures. They are proof that we were awake to the world, even if we couldn't hold on to all of it.

The Comfort of the Un-lived life

There is a strange, seductive comfort in the things we never do. As long as I never actually pick up the drumsticks and sit behind a kit, I can maintain the pleasant delusion that I am a dormant rhythmic genius. The potential remains pure, untainted by the messy reality of missed beats, dragging tempos, and the sheer physical awkwardness of limb independence. In the safety of my own head, the book I never wrote is a bestseller. The business I never started is a Fortune 500 company. The screenplay is perfect.

The moment we drag these ideas out of the graveyard and into the daylight, they become subject to the harsh physics of our actual abilities. And that is a terrifying prospect. So we keep them buried. We hoard these phantom futures like emotional insurance. If my academic career implodes, or if I simply get tired of grading papers, I can tell myself, "Well, I could have always been a high-powered corporate lawyer." It is a comforting fiction, a backup generator for our self-esteem that we never intend to switch on. It protects us from the stinging possibility that we might try something new and be completely average at it.

But beyond the fear of mediocrity, there is a colder, harder truth here. It has nothing to do with fear and everything to do with math. We simply cannot do everything. We live in a culture that tells us we can "have it all," but that is a lie designed to sell planners and energy drinks. A life is defined as much by what we decline as by what we accept. To say "yes" to a tenure-track position in academia is to say "no" to a hundred other lives. We act as if we can keep our options open forever, but time is a door that only swings one way. We are sculptors, and our time is the marble; you have to chip away the parts that aren't the statue, even if those parts were beautiful.

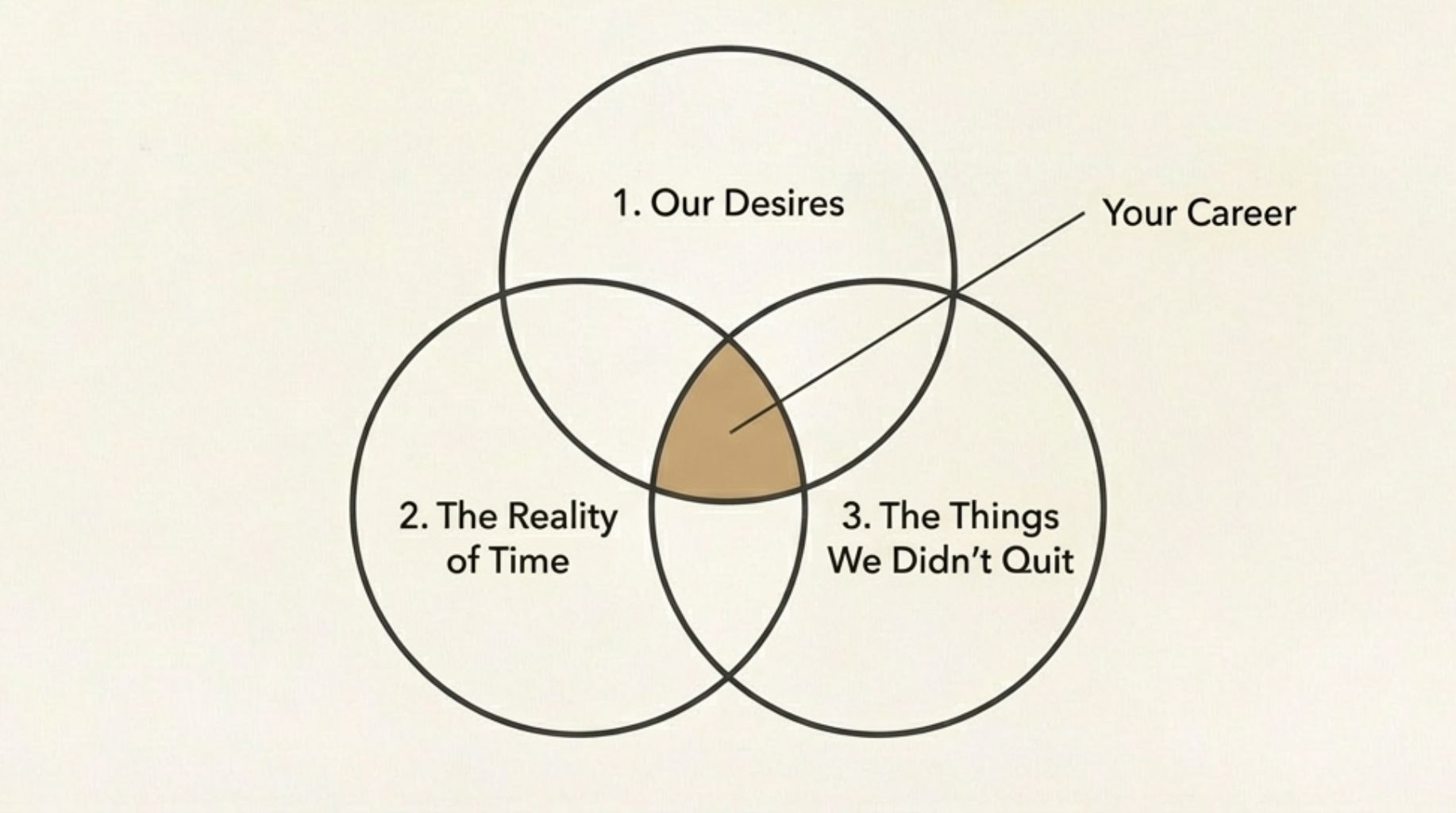

My career, that polished list of accomplishments I present to the world, is not the result of boundless talent or infinite capacity. It is just the tiny, strangely shaped sliver of overlap between my desires, the reality of time constraints, and the things I didn't quit.

Visiting the Graveyard

So, what's the point of walking through this cemetery of half-baked schemes? It might seem pointless to catalogue all the ways I fell short of my own grand visions. But I find a strange utility in rummaging through the graveyard.

For one, it reminds me of who I used to be. That person who wanted to write the next great Jamaican novel or tap dance like Gregory Hines wasn't wrong; they were just optimistic. There is a sweetness to that optimism that I miss sometimes in the daily chaos of grading papers and sitting on committees. It is easy to become cynical when you are dealing with the bureaucracy of a university, to feel like your life has narrowed down to a series of administrative tasks. Visiting the graveyard reminds me that my imagination used to be wider than my job description.

Occasionally, I even pull a corpse out of the ground. No, I am not going to quit my position to tour with a reggae band. That ship has sailed, and frankly, my back hurts too much for van life. But realizing that I still care about rhythm might prompt me to buy a practice pad. I can tap out paradiddles on my desk while I'm on hold with IT support. It is a lower-stakes resurrection. I don’t need to be an expert. I can just be a guy who enjoys making noise.

We tend to treat our abandoned interests as evidence of a scattered mind—a lack of focus or discipline—but I prefer to see them as proof of a wide one. This graveyard isn't a monument to failure. It is an archive of curiosity. It shows that for a brief moment, I looked at a piece of the world—whether it was percussion, or dance, or the legal code—and thought, I want to understand that. I didn't stay long enough to master it, but at least I stopped by.

Join the mail list

Liked this blog? Consider signing up to get a notification for new posts.