- Dec 12, 2025

Could AI do a professor's job? It depends...

- Clive Forrester

- Academia

- 0 comments

Over the past couple of years, whenever I find myself at a dinner party, a backyard barbecue, or really any social gathering where introductions are made, I inevitably go through the same little dance. I meet someone new, we exchange pleasantries, and eventually, the question of "what do you do?" comes up. When I tell them I’m a professor, the reaction is almost always warm. There is still, thankfully, a fair bit of respect for the profession. People generally see professors as experts who have spent years digging deep into some obscure corner of human knowledge, even if that corner seems terribly niche to everyone else.

But lately, that initial moment of respect is quickly followed by a look of concern, or perhaps curiosity. The conversation invariably pivots to Artificial Intelligence. They want to know how the university is holding up against the flood of machine-generated essays. They ask if students are cheating, if I can tell the difference between a human and a bot, and if we’re returning to pen-and-paper exams in chilly gymnasiums just to be safe.

What is surprising, however, is what they don’t ask. In all these encounters, nobody has looked me in the eye and asked, "So, is that computer going to take your job?"

I suspect they are thinking it. It’s the natural follow-up, isn't it? If a machine can write the essays, answer the questions, and arguably organize the syllabus better than I can, why is the university still paying me? Perhaps they are too polite to ask, or perhaps they assume that the ivory tower is the one place safe from automation. But it is a question worth asking, and more importantly, it is a question worth answering honestly.

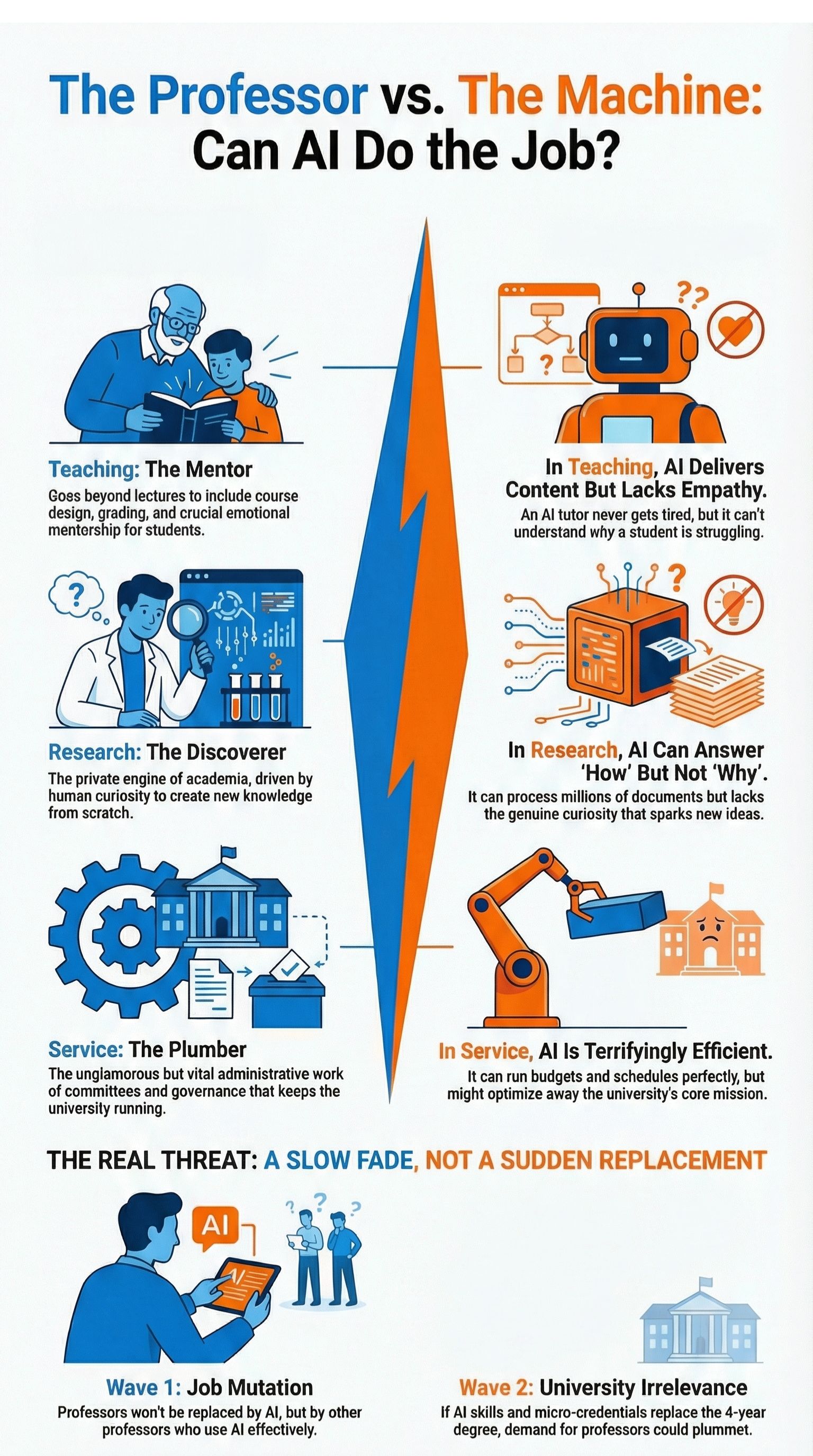

To do that, though, we have to move past the popular image of the professor—the figure standing at a podium delivering wisdom to a silent lecture hall. That is certainly part of it, but if we are going to determine if an AI can do my job, we first need to agree on what my job actually is. It isn't a single task. It is a strange, three-legged stool that supports the academic life: teaching, research, and that catch-all bucket we affectionately, and sometimes wearily, call "service."

If we pull these apart, we might find that the answer to the unasked question isn't a simple yes or no. It depends entirely on which part of the job you’re trying to replace.

So what does a professor do?

Let’s start with the leg everyone sees: teaching. To the casual observer, this looks fairly straightforward. I stand in front of a room, I talk about linguistics, and hopefully, the students write down the important bits. But the lecture is really just the final ten percent of the work. The rest is the invisible, often tedious labor of preparation. It is the hours spent designing the course, figuring out how to explain a concept like "syntax" to a room full of people who have never thought about sentence structure in their lives. It involves grading, which is less about checking boxes and more about trying to decipher what a student meant to say versus what they actually wrote. And then there is the mentoring—the panicked emails at midnight, the students crying in my office because they are overwhelmed, and the long conversations where we try to figure out what they want to do with their lives. Teaching is as much emotional labor as it is intellectual delivery.

Then there is research. If teaching is the public face of the job, research is the private engine. This is the part of the job that actually got most of us hired in the first place. It isn't just "conducting research" as if we are following a recipe book. It starts with a nagging curiosity, a question that won't let you go. It involves digging through archives, crunching data sets that make your eyes cross, or staring at a blank screen trying to wrestle a chaotic mess of ideas into a coherent argument. Research is the act of creating new knowledge where none existed before. It is slow, often frustrating, and filled with dead ends. But it is also the only way we push the discipline forward. We don't just read books; we write them.

Finally, we have service. This is the part of the job description that usually elicits a groan from faculty and a blank stare from everyone else. Service is the university’s plumbing. It is the unglamorous, necessary work of governance. It means sitting on committees to decide on curriculum changes, hiring policies, or admissions standards. It involves hours of meetings where we debate the precise wording of a policy document that very few people will ever read. It is the bureaucracy that keeps the institution running, the endless "peer review" of the university itself. It is dull, it is time-consuming, and it is absolutely vital if we want the university to be run by scholars rather than just managers.

So, we have the teacher-mentor, the curious researcher, and the committee-sitter. It’s a strange mix of skills for one person to hold. And it begs the question: how many of these hats can an AI wear?

The Match-Up: Professor vs. The Machine

To be fair to the machine, let's set some ground rules. We aren't talking about AI as a helpful assistant that writes my emails or double-checks my citations. We are talking about replacement. Can the machine do the job autonomously?

If we look at teaching, specifically the delivery of content, I have to concede a point to the AI. If the job is simply to transfer information from one database to a student's brain, the AI wins hands down. We are already seeing "AI-first" approaches popping up, like the University of Wyoming's recent commission to overhaul their entire teaching strategy around these tools. An AI tutor never gets tired. It doesn't get frustrated when you ask the same question for the tenth time. It can switch modalities instantly—explaining a concept with text one minute, a diagram the next, and a quiz the minute after that, all perfectly fine-tuned to the student's level. I have days where I’m tired, distracted, or just not explaining things well. The machine is always "on." But teaching is more than just a content dump. The human element—the shared struggle of learning, the empathy—is missing. An AI can explain the mechanics of a sentence, but can it understand why a student is struggling to write it? Probably not.

Then there is service. This is where the efficiency argument gets terrifyingly strong. An AI could manage university scheduling, budgets, and strategic planning without the need for hundreds of hours of committee meetings. It wouldn't need coffee breaks, it wouldn't argue about the font size on the syllabus policy, and it could draft a five-year strategic plan in seconds. In fact, Duke University engineers recently built an AI microscope platform that runs its own experiments autonomously—if we can trust AI to run a lab, we could certainly trust it to run a meeting. The danger, of course, is that what looks like efficiency to an algorithm might look like a disaster to a faculty member. An AI optimization model might decide that the most "efficient" university is one with massive class sizes, zero humanities departments, and economic viability as the only metric that matters. It would be efficient, yes, but it might cease to be a university.

Finally, we have research. On paper, the AI is a formidable opponent here too. It can scan millions of documents, find gaps in existing knowledge, and crunch numbers better than I ever could. We are seeing "self-driving labs" where AI agents generate ideas and run experiments without human intervention. But here is the snag: why would it? Research is driven by curiosity, by that nagging "why" that keeps us awake at night. There is no evidence that an AI is curious. It has no motivation to follow a hunch or to prove a hypothesis just for the satisfaction of knowing the answer. It could do the research, certainly. But without a human asking the questions, there is no reason why it would.

The Slow Fade

So, is the professor safe? For now, I think the answer is yes, if only for the brutally pragmatic reason that students—or rather, their parents—are unlikely to pay tuition for a chatbot. There is a certain stubborn value in the "credential," the piece of paper that says you learned from a human expert. No one is going to take out a student loan to be taught by an app they can access on their phone for free. The economics of the university, precariously balanced as they are, still rely on the warm body at the front of the room.

However, I suspect the real threat won't come from a robot walking into my office and taking my keys. It will be subtler than that. It will come in two waves.

First, the job itself will mutate. In the not-so-distant future, AI literacy will stop being a novelty and start being a mandate. We saw this during the pandemic, and later with the various cultural shifts in academia, where new hires were suddenly expected to have a "decolonizing strategy" or a specific diversity statement as part of their teaching philosophy—whatever the administrative flavor of the month happened to be. It will be the same with AI. The professors who can deftly weave these tools into their pedagogy will edge out those who refuse to open the software. We won’t be replaced by AI; we will be replaced by professors who use AI.

The second wave is more existential. As university education becomes increasingly viewed as an expensive gamble, the market might simply shift. If a student can gain "AI competence"—the ability to wrangle these massive systems—through a series of cheap micro-credentials, the traditional four-year degree might lose its luster. We are already seeing employers, including tech giants, dropping degree requirements in favor of demonstrated skills. If the pathway to a good job is no longer a degree but a portfolio of AI certifications, the demand for professors drops off a cliff. The AI doesn't need to take my job directly; it just needs to make the university irrelevant. In that scenario, the professorate doesn't disappear with a bang, but with a slow, quiet downsizing.

Will it happen? Only time will tell. But until then, I have a committee meeting to get to. I wonder if ChatGPT can take the minutes?

Join the mail list

Liked this blog? Consider signing up to get a notification for new posts.