- Jan 24, 2026

The Slow Academic: Why Quality should trump Quantity in Academia

- Clive Forrester

- Academia

- 0 comments

At the start of 2024, I published two books. One arrived at the very end of 2023, and the other followed in January. They were both edited volumes, and I co-authored one with a colleague. To an observer, this might look like a sudden burst of productivity, but the record before that tells a different story. In 2022, I had exactly one publication in a little-known book. In 2021, there was nothing. My previous entry before that was in 2020.

I am a "teaching stream" professor at my institution. This means my time is officially earmarked for the classroom rather than the laboratory or the library archives. Teaching has a higher priority than research. But even within that framework, I have settled firmly into the "slow academic" camp.

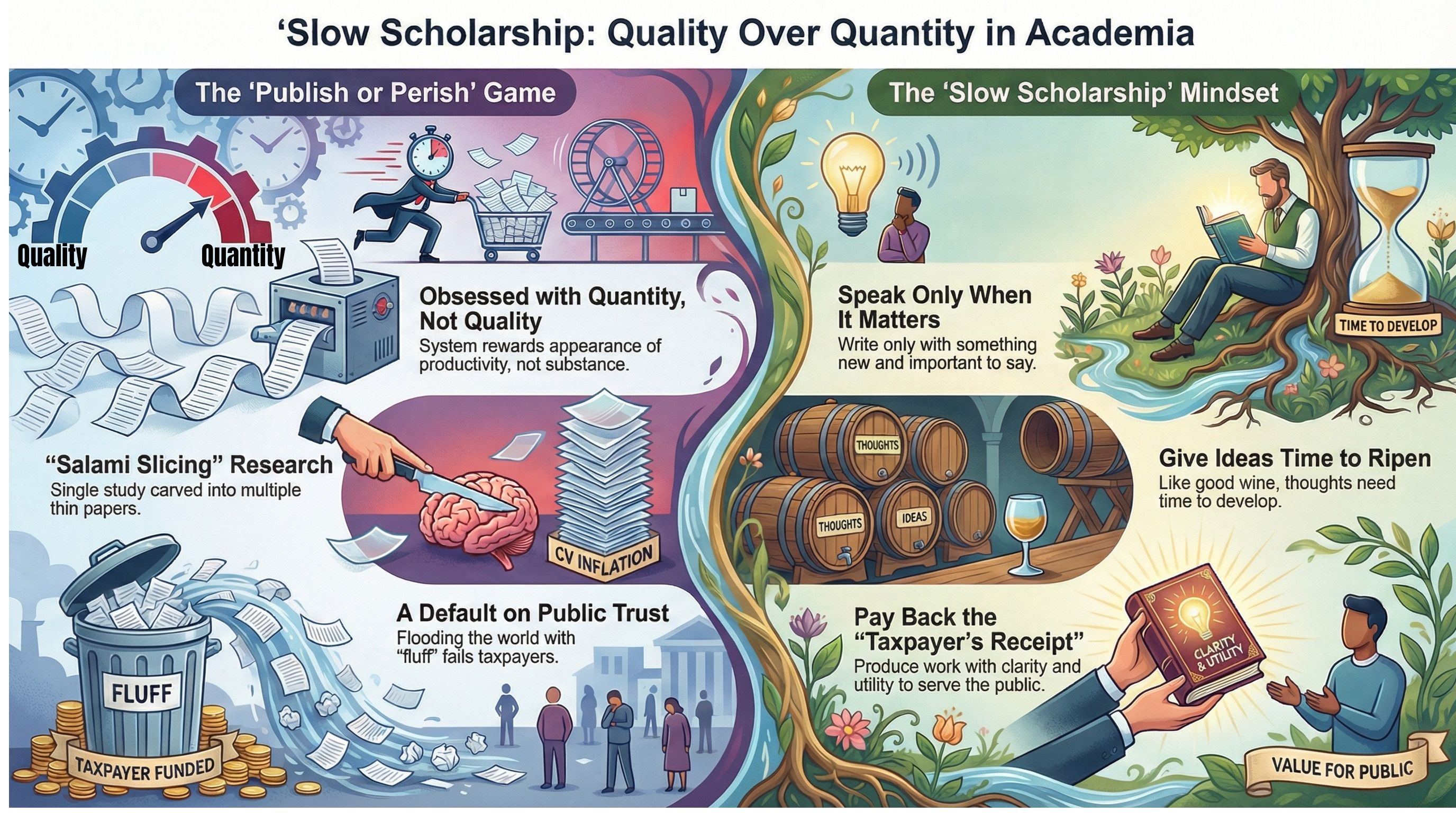

I take a deliberate approach to what I put into print. I write when I have something to say that hasn't been said before, and I stay silent when I don’t. Otherwise, I am focused on my students and enjoying a regular life. I do not chase "metrics"—a confession that feels almost heretical in modern academia. To be honest, I couldn't care less. Our field is currently littered with so many garbage publications that the last thing I want to do is add to the landfill.

II. The Taxpayer’s Receipt

Most people will go through their entire lives without ever opening an academic journal. They won't read my co-authored volume on language rights, and they certainly won't care about the "metrics" I mentioned earlier. On the surface, it can seem like a private, rather expensive conversation between a few hundred people tucked away in ivory towers. But that is an illusion.

The ideas generated in these quiet offices eventually find their way into the streets. They shape the policies written in government buildings, the way we debate social issues on the news, and sometimes, the very way we perceive reality itself. Whether it’s how we understand the shifts in language or how we structure our legal systems, academic thought trickles down into the public consciousness. When an academic does their job well, they provide the tools for society to understand how it works.

Because of this influence, there is a silent agreement—a social contract—between the university and the public. We aren't just here to talk to each other; we are here to serve a broader purpose. It is easy to forget that most of my time, and the time of my colleagues, is bought and paid for by the public through their taxes. Every time someone pays their taxes, they are, in part, investing in the collective intelligence of their community.

We owe a specific debt to the people outside the campus gates. It's a debt that we can only pay back through work that has clarity and utility. If we are being funded to think, then we have a moral obligation to ensure that our thoughts are actually worth the paper they are printed on.

Returning value to society isn't about the number of pages we produce. It isn't about filling up a CV or "disseminating"—to use a word that sounds more like a biological process than a conversation—our work for the sake of appearances. It is about making sure that when we finally do speak, we are offering something that can actually be used to make the world a slightly more sensible place. If we flood the public with fluff just to meet an institutional quota, we aren't just being busy; we are defaulting on our debt to the very people who make our work possible.

III. The Broken Game of "Publish or Perish"

On the matter of fluff and gibberish research, this has been an ongoing problem in academia. It is an open secret that we have allowed our primary purpose—the pursuit of knowledge—to be hijacked by a system that resembles a poorly designed video game. In this game, "impact factors" and citation counts are the high scores, and many of us are playing as if our careers depend on achieving a new "level" every year.

The "publish or perish" paradigm has shifted from a cautionary tale into a rigid operational manual. It has led to a kind of gamification where the goal is no longer to solve a problem or illuminate a dark corner of human experience. Instead, the goal is simply to keep the bar moving. We have become obsessed with the appearance of productivity rather than the substance of it. When a faculty member’s worth is calculated by the number of entries on their annual report, they are incentivized to value quantity over quality.

One of the most visible symptoms of this is "salami slicing." This is the practice of taking a single, meaningful study and carving it into three or four separate, thin papers. On a CV, this looks impressive—four lines of text instead of one. For the reader, salami it is a frustrating experience. You are forced to track down several different articles to get a complete picture that could have been painted in a single, well-crafted piece. It serves the professor’s promotion file, but it starves the public record. Here's another example of how this is done. Remember earlier I spoke about two publications? What if I told you there's a way to count them as six? Yes--two edited volumes, plus a chapter in each of them, plus the introductions to the books which I wrote myself - voila! What once was two, is now six.

This kind of CV padding is essentially intellectual fluff masquerading as contribution. When we focus on the score, we stop focusing on the truth. A scholar who produces ten mediocre papers a year isn't necessarily more valuable than the one who spends five years on a single, groundbreaking book. Yet, the system is rigged to reward the former. We have created a culture where the "garbage" I mentioned earlier isn't just a byproduct; it’s the required fuel for a career. We are so busy keeping our heads above the water of these metrics that we have forgotten how to swim.

IV. The Case for the Unhurried Mind

This isn't a call for laziness. If anything, the "slow" method is far more demanding than the alternative. It is easy to churn out ten pages of jargon that says very little; it is incredibly difficult to sit with an idea for three years until it finally makes sense.

Admittedly, choosing this path is scary. In a system that counts beans, if you don't show up with a full bag every year, you run the risk of looking like a failure. It might mean a longer wait for the title of "Full Professor." It means your annual report might look a bit thin compared to the colleague next door who is slicing their research into thin ribbons. You have to be comfortable with the silence of the years where you publish nothing.

But there is a reward in that silence. Going slow allows an idea to actually ripen. Like good fruit or a well-aged wine, some thoughts simply cannot be rushed. When we step off the treadmill, we give ourselves the space to be thinkers rather than factory workers. We reduce the soul-crushing burnout that comes from trying to meet a quota that has nothing to do with truth and everything to do with administration.

More importantly, we increase the chance that when we finally do speak, we are offering something that lasts. We should want our work to stay relevant for decades, not just for the few weeks it spends on a "New Publications" shelf.

At the end of my career, I don't want to look back at a long list of titles that I barely remember writing and that no one bothered to read. I would rather have a handful of works—like those two books on my desk right now—that I know were worth the time they took to produce. In a world that is moving much too fast, perhaps the most ambitious thing a scholar can do is take their time. We owe it to the public, and we certainly owe it to ourselves, to make sure our words carry some weight.

Join the mail list

Liked this blog? Consider signing up to get a notification for new posts.